At 15,000 feet, the world becomes a vortex of fog, ice, and impenetrable forest. As trail runner Laura Cortez emerged from a mile-long army crawl through dense brush in search of the trail to Mexico’s 17,000-foot Iztaccíhuatl volcano summit, she met the alpine sun and clouds racing to obscure it.

She scanned the Mars-like expanse before her, knowing the wrong turn she’d made earlier may have closed her window of opportunity to complete the city-to-summit FKT attempt she’d spent months training for. Every moment she hesitated, her situation grew more dire. As her ego screamed for her to push through and prove herself, a quieter voice grew stronger: her father’s.

“My dad was my ego check all the time,” Laura recalls. An athlete himself, Richard Cortez was Laura’s biggest fan and anchor to values deeper than winning, like sportsmanship and gratitude. As her trail running career took off, his guidance was impactful, if puzzling. “He’d always tell me to make sure I take a minute to thank the universe” — advice that seemed out of place from her conservative father, but ultimately, “he planted the seed in my head that sport is more than just about winning.”

Born second-generation Mexican-American in South Texas, Richard often visited his parents’ hometown of Amecameca growing up. This deeply traditional town of about 50,000 sits 50 miles from Mexico City at the foot of the myth-shrouded volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl, known affectionately as ‘Popo’ and ‘Izta.’

While her father grew up in proximity to Mexico, Laura’s parents always discouraged her and her brother from visiting, citing safety concerns. Laura didn’t grow up speaking Spanish and recalls little emphasis on embracing their cultural identity due to stereotyping and prejudice against Latinos in the US.

Even so, Richard never shied away from helping Laura understand her heritage, which over time encouraged in her a deeper curiosity. “So much of what brought me comfort in my ties to Mexico stemmed from him. All my questions about childhood and culture were answered by him.” Without a personal relationship to Mexico, Richard was not only her athletic mentor, but her strongest tether to her family’s heritage.

“He’d always tell me to make sure I take a minute to thank the universe. He planted the seed in my head that sport is more than just about winning.”

That’s why when he died in 2023 after decades of smoke inhalation as a firefighter, she felt a void in her identity bigger than she’d expected. She lost the person with whom she explored meaning in sport and heritage. “I didn't realize that he was the tether to everything – from food to language to jokes to pop culture. It hadn't really occurred to me, and that was horrifying.”

So began her journey to find the connection her father once brought her. When an

opportunity arose to design a trail running project of her choosing later in 2023, she knew she wanted to do it in Amecameca to finally explore her family’s roots.

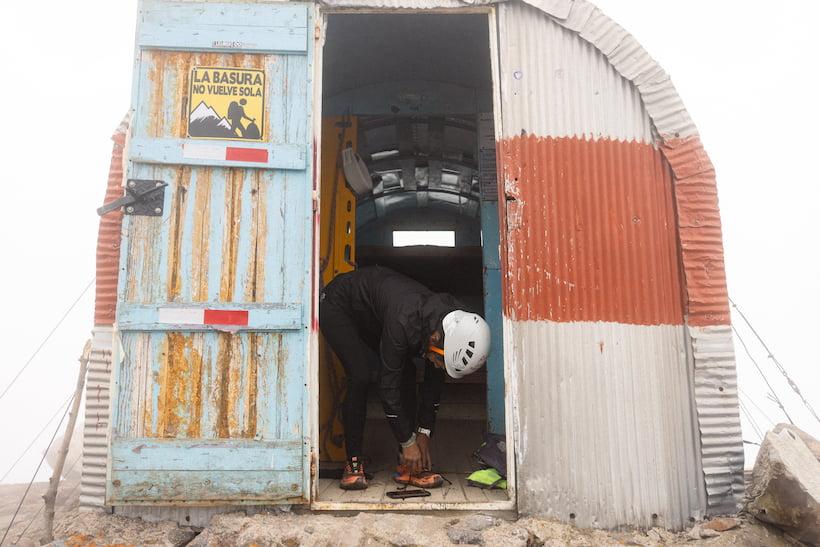

She chose to take on the city-to-summit trail from Amecameca to Izta, tracing the path that archeological evidence suggests had been taken by Mesoamerican peoples for centuries. The goal was to complete the 12-mile, 9,000-foot elevation gain trail to the summit in under four hours. This expedition is difficult, with glaciers, class 2-3 scrambles, and route-finding demands.

Over the next few months, she paid repeated visits to Amecameca to train. During those first visits, Laura leaned into the love she’d always felt from her Mexican family to ease her anxiety and imposter syndrome. Even though her extended family had since moved to Mexico City, she felt her father’s presence there. Visiting the places he’d told her about and being embraced with warmth and acceptance by the locals made every day she spent there feel like “a welcoming hug” that deepened her understanding of her father’s values.